Subsidized employment is a promising strategy for boosting incomes and improving labor market outcomes and well-being, especially for disadvantaged workers. This report represents findings from an extensive review of evaluated or promising subsidized employment programs and models spanning four decades that target populations with serious or multiple barriers to employment in the United States.

Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Initializations

Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Initializations

ABE — Adult Basic Education

ACF — Administration for Children and Families of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

ACF OPRE — Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families

AFDC — Aid to Families with Dependent Children

ARRA — American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Recovery Act)

CBPP — Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

CETA — Comprehensive Employment Training Act

DOL — U.S. Department of Labor

EITC — Earned Income Tax Credit

ETA — Employment and Training Administration of the U.S. Department of Labor

ETJD — Enhanced Transitional Jobs Demonstration of the Employment and Training Administration, U.S. Department of Labor

GA — General Assistance

GED — General Education Development test

HHS — U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

JSA — Job Search Assistance

OJT — On-the-Job Training

PSE — Public Service Employment

SNAP — Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; also referred to as “food stamps”

SSA — Social Security Administration

SSDI — Social Security Disability Insurance SSI — Supplemental Security Income

STED — Subsidized and Transitional Employment Demonstration Project

TANF — Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

TANF EF — Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Emergency Fund

TJRD — Transitional Jobs Reentry Demonstration

UI — Unemployment Insurance

WIOA — Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act

WOTC — Work Opportunity Tax Credit

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Subsidized employment is a promising strategy for boosting incomes and improving labor market outcomes and well-being, especially for disadvantaged workers. This report represents findings from an extensive review of evaluated or promising subsidized employment programs and models spanning four decades that target populations with serious or multiple barriers to employment in the United States. It includes a framework aimed at helping practitioners develop more innovative and effective programs by identifying key elements of program design and implementation; a review of relevant models from the past 40 years, including key findings from this research; and a set of recommendations for policymakers and practitioners for further utilization of subsidized jobs programs.

The goal of this paper is to promote subsidized employment policies and programs that are likely to increase quality opportunities for individuals with serious or multiple barriers to employment, during both

economic expansions and contractions.

The report examines several types of programs that address in an integrated way both labor supply anddemand to directly increase paid work among disadvantaged workers.1 The main focus is on subsidized employment programs that offer subsidies to third-party employers—public, non-profit, or for-profit—who in turn provide jobs to eligible workers. As shown in the table below, subsidized employment programs are versatile tools that, depending on factors such as the timing of the business cycle and the target population, can be adapted accordingly. The employment they provide may be temporary and countercyclical, temporary and part of a strategy to help people shift to unsubsidized employment (regardless of the macroeconomic situation), or long-term for people who need long-lasting subsidies. The experiences offered by transitional (not long-term) subsidized jobs—in terms of what they expect of employees, how well employees are compensated, and the employment and labor rules the employers must follow— conform to or closely mimic competitive employment. This report focuses particularly on the second and third strategies, though the first strategy can provide important opportunities for disadvantaged workers, even if it is deployed more broadly.

In addition, this report examines some notable paid work experience programs, which may provide some compensation for training or work activities, but do not necessarily involve third-party subsidies, and may not conform to typical experiences in competitive employment. The report also reviews selected community service models, which are often not intended to mimic competitive employment but instead provide opportunities for modest work activity and nominal stipends, where appropriate. Finally, the report profiles several unsubsidized employment programs, which do not offer funding for third-party employers, as well as intensive youth-only employment programs that provide relevant lessons for subsidized employment models.

Three Overarching Subsidized Employment Program Strategies

| Duration of Subsidized Employment | Timing in Business Cycle | Target Population | Primary Purpose | Demands on Workers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 | Transitional Employment | Anti-recessionary* | Long-term unemployed; low-income | Income support; increasing employment | Identical to unsubsidized employment |

| Strategy 2 | Transitional Employment | Permanent | disadvantaged workers with serious or multiple barriers | Increasing employment | Eventually approximating unsubsidized employment |

| Strategy 3 | Long-Term Employment | Permanent | Disadvantaged workers with serious or multiple barriers | Income Support | Significantly less than subsidized employment |

Subsidized Employment as a Promising Tool

As this report outlines, there are multiple, interrelated rationales underlying subsidized employment, all of which lead to different program designs. First, subsidized jobs offer a vehicle for providing incomes in exchange for productive work. In addition, subsidized jobs can reduce the risk an employer perceives or the cost they may experience from hiring a worker or increasing a worker’s earnings, employment, or income. These programs can also lead to even further-reaching gains for the well-being of participating workers and their families.

While aggregate labor demand policies—both fiscal and monetary—are essential to helping low-income workers secure and maintain sufficient employment, additional policies and programs would be valuable throughout the business cycle for those with serious or multiple barriers to employment.2 Subsidized employment programs and policies are underutilized, potentially powerful tools for lifting up workers in or at risk of poverty and deep poverty in the United States. These job programs can provide income support, an opportunity to engage in productive activities, and, in some cases, labor market advancement opportunities. They can also offer a platform for connecting people to other needed services, resources, and networks.

The potential benefits of these models provide a straightforward economic rationale for public investments. Insofar as increasing employment and work experience provides benefits to the individual and society (such as improved health, strengthened families, and reduced demand for public benefits and services) not fully captured by the compensation employers are willing to offer non-employed workers, there is a rationale for public subsidies. Employers by and large do not set compensation levels based on social benefits to hiring.

Program Design Framework

This report includes a framework that describes key elements of subsidized employment programs. Programs can differ along a number of dimensions, each of which are likely to affect program effectiveness. These include program purpose (target populations3 and barriers, competitive employment vs. income support, and scale); work placements (sector, employer size, long-term placement strategy, employer of record/payroll, and advancement opportunities); subsidy configuration (type, depth, and length of subsidy); work expectations (supervision, team environment, and graduated responsibilities); training (type and structure of training); and additional services (wraparound and employment search and retention services). The focus of this report is individuals with serious and/or multiple barriers to employment, which is often the target population of subsidized employment programs. For the purposes of this report, barriers to employment are broadly defined as limitations—real or perceived—that significantly reduce the likelihood of attaining competitive (unsubsidized) employment. These personal and institutional barriers reflect a complex mix of socioeconomic dynamics, which can manifest as skill limitations; physical and behavioral health issues, including disabilities; criminal justice system involvement; family obligations; limited resources; and discrimination based on characteristics such as race, gender, and age, among others.

Next Steps

Forty years of experience suggests that subsidized employment programs warrant significantly greater attention from policymakers and practitioners. Despite their track record and promise, available funding for subsidized employment programs is meager when compared to the potential efficacy of and need for these programs. While there is still a need for more experimentation with subsidized jobs programs, especially for subpopulations with multiple and/or serious barriers, much experimentation is currently underway; moreover, enough is known today for a significant, national effort to expand subsidized employment programs.

This report concludes with five recommendations (summarized on the following page) for policymakers and legislators at the federal, state, and local levels to take into account when designing, modifying, or furthering subsidized employment policies and programs:

-

Make Subsidized Jobs Programs a Permanent Part of U.S. Employment Policy

Despite nearly a half-century of supportive evidence, subsidized employment today is significantly under-recognized and underutilized as an effective anti-poverty tool. Policymakers should prioritize making such programs a permanent part of U.S. employment policy. Such programs could and should make up a core component of a broad-based, ongoing strategy to combat poverty, reduce inequality, and ensure that every person wanting to work has access to a decent job at any point in the business cycle. Having a program in place during an economic expansion also likely improves the ability to scale it up to meet growing need during the next recession.

-

Establish Substantial, Dedicated Funding Streams

Many previous and current subsidized employment programs have drawn funding from existing federal programs not primarily dedicated to subsidized employment. The lack of substantial, dedicated funding streams likely has severely limited the scale and scope of these programs, as well as needed innovation. Dedicated subsidized employment funding streams may allow for greater flexibility, help encourage administrative and programmatic innovation, and provide the resources necessary for such programs to make meaningful headway against poverty.

-

Ensure Opportunities for Advancement

For workers likely to eventually succeed in the competitive labor market, subsidized employment should offer meaningful career ladders, a chance to develop skills through educational and training opportunities, and the possibility for advancement through increased responsibility and compensation over time. With the goal of supporting robust career paths in mind, subsidized employment should be developed in parallel with education and training initiatives that forge meaningful and sustainable connections between participants and the labor market. Multiple paths (as well as multiple entry and exit points within each path) with the ability to tailor specific programs and supports to particular participants should also be considered.

-

Promote Program Flexibility

This report documents an array of key program design parameters, including whether to subsidize transitional jobs or potentially permanent positions; whether and how to engage the for-profit, non-profit, and public sectors; and which portfolios of wraparound services to offer to which participants. The greatest takeaway is that the best answer will vary across place, target population, and other factors. Therefore, program funding should be sufficiently flexible to allow programs to adjust to local dynamics and changing circumstances while keeping the needs of participants and employers paramount.

-

Facilitate Greater Innovation

Despite the proven success of many programs under an array of economic circumstances and for many diverse populations, continued exploration in the forms of pilot programs, demonstrations, cross-sector collaboration, and studies is necessary in order to most effectively target subpopulations and communities. For workers with especially long paths to competitive employment and those whose ultimate goal is something short of competitive employment, strategies should include and encourage experimentation with programs that provide part-time paid work experience options. Combining subsidized jobs and paid work experience programs with other interventions, such as those that focus on executive function5, financial coaching and savings, behavioral health, and vocational rehabilitation may further improve economic outcomes for participants.

To be sure, subsidized employment programs are neither silver bullets for all labor market challenges nor fully mature yet for every reasonable target population of disadvantaged workers. In addition to strong macroeconomic policy, there is no substitute for worker empowerment or strong labor standards such as well-enforced employment protections that prohibit discrimination, especially when it comes to very disadvantaged workers. At the same time, more thinking and action is clearly needed to develop more effective subsidized employment and paid work experience programs for a wide range of populations. However, the record as it stands already indicates that such programs, by increasing employment opportunities, can be effective tools to combat poverty, persistent unemployment, and other undesirable social outcomes. The research in this paper confirms this and points to the need for subsidized employment to become a key component of a broader agenda promoting quality and sufficient employment for all who are willing and able to work.

Introduction

Introduction: Subsidized Employment as a Promising Tool

Subsidized employment is a proven, promising, and underutilized tool for lifting up disadvantaged workers—particularly those in or at risk of poverty or with serious and/or multiple barriers to employment. These job programs can provide income support, an opportunity to engage in productive activities, and, in some cases, labor market advancement opportunities. They can also offer a platform for connecting people to other needed services, resources, and networks. A number of models have shown positive impacts according to the highest standards of evidence; there are also a number of innovative models that appear promising for improving outcomes—even for groups not previously helped by these programs. In addition to promoting work among adults struggling in the labor market, subsidized employment programs can also help strengthen disadvantaged families. Yet, despite their significant potential, at the state and local level program administrators often must cobble together modest public resources to fund these programs. Though this report takes a balanced and careful look at the evidence, it makes clear that policymakers should devote more attention and dedicated resources to take full advantage of subsidized employment as a tool for reducing poverty and expanding opportunity.

This report represents findings from an extensive scan of evaluated or promising subsidized employment programs and models1 spanning four decades that target populations with serious or multiple barriers to employment in the United States.2 It includes a framework aimed at helping practitioners develop more innovative and effective programs by outlining critical elements of program design and implementation; a review of relevant models from the past 40 years, including key findings; and a set of recommendations for policymakers and practitioners for further utilization of subsidized jobs programs.

The goal of this paper is to highlight and promote policies and programs that are likely to increase quality subsidized and supported paid work opportunities for adults with multiple barriers to employment. This report is not primarily about job creation strategies, though subsidized employment can be a useful tool in broader job creation efforts.3

For the purposes of this report, barriers to employment are broadly defined as limitations—real or perceived—that significantly reduce the likelihood of attaining competitive (unsubsidized) employment. These personal and institutional barriers reflect a complex mix of socioeconomic dynamics, which can manifest as skill limitations; physical and behavioral health issues, including disabilities; criminal justice system involvement; family obligations; limited resources; lack of education; limited work experiences; and discrimination based on characteristics such as race, gender, and age, among others.

Keeping in mind that integrating disadvantaged populations into mainstream programs and services may be the most effective strategy in many cases, many of the models profiled in the report directly or indirectly target nine overlapping categories of people who are particularly likely to need subsidies and wraparound services and supports—some temporary and some ongoing—to succeed in the labor market. The nine groups are as follows:

- Disconnected youth;

- People with work-limiting disabilities;

- Single mothers and non-custodial parents;

- People with criminal records;

- Older workers who have been pushed out of the labor market due to economic dislocation;

- Disadvantaged immigrants, especially refugees and asylum seekers;

- Long-term unemployed workers;

- People in areas of particularly high unemployment; and

- People experiencing homelessness.

While aggregate labor demand policies—both fiscal and monetary—that ensure high levels of employer demand for workers in the overall economy are essential to helping low-income workers secure and maintain sufficient employment, additional policies and programs would be valuable throughout the business cycle for those with serious or multiple barriers to employment.4

Research suggests that some workers with serious and/or multiple barriers may benefit from transitional subsidized jobs, but others (such as a portion of those with behavioral health challenges, the most limiting disabilities, or substantial family responsibilities) might require ongoing subsidies and other supports and services for successful job placement and retention in competitive or other meaningful work environments. Depending on the barriers, subsidized jobs may not be the most suitable initial strategy for some individuals. For example, someone with extremely limited education or skills may require other interventions and support well before a subsidized employment placement.

This report examines several types of programs. The main focus is subsidized employment programs that offer subsidies to third-party employers for providing work opportunities to eligible workers. As shown in Figure 1, subsidized employment programs are versatile tools that, depending on factors such as the timing of the business cycle and the target population, can be adapted accordingly. They may be temporary and countercyclical, temporary and part of a strategy to help people get jobs that do not entail extra subsidies (regardless of the macroeconomic situation), or long-term for people who continue to need a subsidy. The experiences offered by these jobs—in terms of what is expected of employees, how well employees are compensated, and the employment and labor rules the employers must follow—conform to or closely mimic competitive employment. This report does not attempt to exhaustively categorize all programs of this nature that have been implemented in recent decades. Rather, it focuses on those programs targeting disadvantaged workers that have been (or are being) rigorously evaluated or have been identified by experts as showing promise. As a result, the report focuses particularly on the second and third strategies, though the first strategy can provide important opportunities for disadvantaged workers, even if it is deployed more broadly.

In addition, this report examines some notable paid work experience and community service programs. These types of programs may provide some compensation for training or work activities, but may not conform to typical experiences in competitive employment.5 Finally, the report reviews selected unsubsidized employment programs that target disadvantaged groups, as well as intensive youth-only employment programs that may offer relevant lessons for subsidized employment programs.

Figure 1. Three Overarching Subsidized Employment Program Strategies

Duration of Subsidized EmploymentTiming in Business CycleTarget PopulationPrimary PurposeDemands on Workers

| Duration of Subsidized Employment | Timing in Business Cycle | Target Population | Primary Purpose | Demands on Workers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 | Transitional Employment | Anti-recessionary* | Long-term unemployed; low-income | Income support; increasing employment | Identical to unsubsidized employment |

| Strategy 2 | Transitional Employment | Permanent | disadvantaged workers with serious or multiple barriers | Increasing employment | Eventually approximating unsubsidized employment |

| Strategy 3 | Long-Term Employment | Permanent | Disadvantaged workers with serious or multiple barriers | Income Support | Significantly less than subsidized employment |

Rationales for Programs and Public Financing

There are multiple, interrelated theories underlying publicly supported subsidized job programs, as shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Rationales for Subsidized Employment Programs and Public Financing

| Rationale | Potential Subsidized Employment Program Mechanisms | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| From the perspective of: | Disadvantaged Individuals and Families | Higher income and employment | Immediate employment and income unavailable through unsubsidized employment; stronger families (higher child support payments paid by participants, lower divorce rates, higher marriage rates); reduced criminal justice system interaction for adults and children; improved health for adults and children; work experience, training, and wraparound services offer potential for longer-term gains in labor market and other domains |

| Employers | Lower costs and risks for employing disadvantaged workers | Wage, OJT, or overhead subsidies for hiring targeted workers; subsidies, work experience, and wraparound services lead to larger and more productive workforce immediately and in the future | |

| Government | Higher tax receipts; lower expenditures | Higher taxable incomes for adults and children; higher economic output from work done by participants; improved population health for adults and children; reduced criminal justic system expenditures on adults and children. |

The rationale for subsidized employment may vary based on economic circumstances. For example, during economic contractions, public subsidized jobs programs can play a countercyclical role by increasing employment and the incomes of working families, which is accomplished by making it more affordable for employers to hire workers. Even when the economy appears to be achieving full employment, subsidized employment programs can still reach the disadvantaged individuals who want to work but who struggle to secure and maintain sufficient and stable employment. Under any economic circumstance, these programs may serve a valid purpose by transferring resources to disadvantaged workers and their families in a socially and politically palatable manner.

From the worker’s perspective, subsidized employment provides immediate income support and work (and sometimes training) opportunities. One immediate effect of these programs is to increase earnings and employment during the time of participation. They can also provide a chance to build up recent work history and develop new skills, which may in turn help convince future employers that the participant is capable of being productive and reliable. Some programs may offer formal classroom-based or on-the-job training (OJT) in both soft and hard skills, raising a given worker’s productivity and the market value of his or her labor.

One basic rationale for subsidizing work is to reduce the cost of a job to a given employer, and thus increase the marginal demand for labor. In addition, by reducing the marginal cost of hiring a worker, employers may find it more affordable to invest in some workers through training and education in ways that eventually raise employees’ productivity enough to warrant competitive compensation.

A similar rationale centers on reducing potential risks for employers, particularly when they hire an individual with what the employer perceives to be a barrier to employment (for example, a spotty work history, a disability, or a criminal record). To the extent that such barriers raise or are perceived to raise the marginal risk to potential employers, subsidies can mitigate that risk, by giving employers the opportunity to review workers’ behavior and added value while committing fewer resources than otherwise.

From the government’s perspective, insofar as increasing overall employment and work experience provides benefits to the individual and society (such as improved health, strengthened families, and reduced demand for public benefits and services) not fully captured by the compensation employers are willing to offer non-employed workers, there is a rationale for attempting to deliver public subsidies. In addition, just as direct public employment can finance productive activity, such as the provision of public goods, subsidized employment can similarly result in valuable goods and services that are being under produced by market forces.

To be sure, there are potential downsides to this approach to raise employment levels, including concerns about relative cost-effectiveness and the use of public money to subsidize (indirectly) private profits— insofar as placements are with private for-profit employers. The potential problem of “substitution” of subsidized workers in place of unsubsidized workers requires special attention, as it can be challenging to target subsidies such that they encourage the creation of new jobs (or the maintenance of jobs that otherwise would have been eliminated) rather than displacing one group of workers in favor of another.

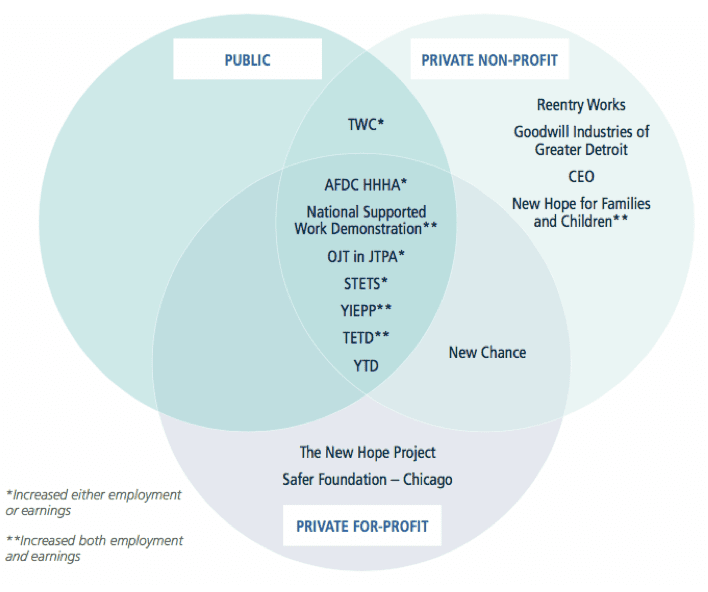

Targeting Both Labor Supply and Demand Through Integrated Approaches

Figure 3 below identifies three common approaches to subsidizing employment for disadvantaged populations. The labor demand approach attempts to drive up demand in the labor market by lowering employers’ hiring costs. The labor supply approach looks to strengthen incentives for workers by increasing the rewards from employment. Integrated approaches, which are the focus of this report, directly raise both labor supply (offering direct wage and other supports and services to workers) and labor demand (offering employment, wage, or OJT subsidies to employers). These integrated approaches also allow for more wraparound supports and services for workers.

This report excludes large-scale employer hiring subsidies structured as entitlements like the Work Opportunity Tax Credit (WOTC). Such credits are generally considered fairly inefficient, due to a large share of their value typically going to employers for hires that would have been made without the subsidy.6 They are also less likely than alternative subsidy designs to help the most disadvantaged workers.7 Notably, focusing on those least likely to be employed will necessarily tend to limit windfalls to employers,8 and may reduce negative effects that stem from stigmatizing workers.9 Careful policy design can help mitigate any concerns about targeted subsidized jobs programs potentially displacing some unsubsidized workers who otherwise would have been hired into the positions of subsidized workers.

The report also excludes the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and other large-scale standalone employment and earnings subsidies that are paid directly to workers without additional supports. Though these subsidies are enormously important for some families with multiple barriers to employment, they do not directly help address those barriers, apart from supplementing low pay.

Figure 3. Common Approaches to Subsidized Employment Policy

| Tax-Based Programs* | |

|---|---|

| Labor Demand Approach | Labor Supply Approach |

| Large-scale programs offering labor cost subsidies to employers (e.g. WOTC) | Large-scale programs offering earnings subsidies to workers (e.g. EITC) |

| Grant Programs | |

| Integrated (Labor Demand and Supply) Approach | |

| Small- to medium-scale programs offering compensation or OJT subsidies to employers (labor demand) and direct wage and other supports and services to workers (labor supply) | |

Framework for Program Design

Overview

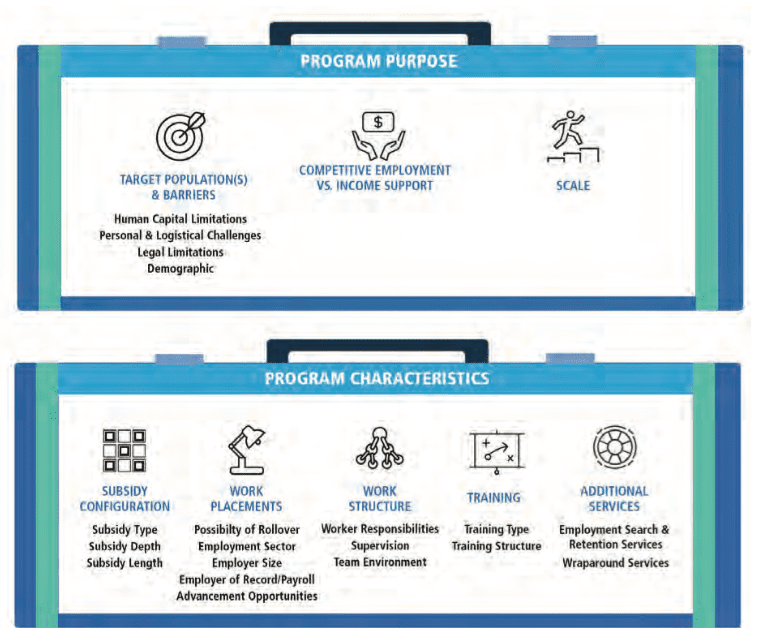

This section lays out a broad framework aimed at helping practitioners develop more innovative and effective subsidized employment programs. The framework identifies key components, parameters, and decision points for subsidized employment programs, as outlined in Figure 4 below.

This section explores potential variations among programs, offering practitioners and program developers a clear framework for design options and trade-offs with regard to helping the most disadvantaged workers. For example, this framework notes how subsidized employment programs differ by the structure and type of work experience and subsidy provided, as well as by intensity (expectations of the worker and employer) and duration.

Figure 4. Core Elements of Subsidized Employment Programs

Source: Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality.

Program Purpose

A particular program’s objectives, especially regarding target populations, intended outcomes, and scale, will substantially influence the design of the program.

Target Population(s) and Barriers

The chosen target population(s) for any program will have implications for program design. To be sure, many people face multiple barriers that cut across the categories described below. Therefore, effective programs may be those that are able to address a wide range of potential barriers regardless of the targeted population(s). The needs of and most promising opportunities for young single mothers are likely to be different from those of men with criminal justice involvement, for example. At the same time, both groups may face human capital and behavioral health challenges. This section explores the overlapping barriers that these populations and others face.

Keeping in mind that integrating disadvantaged populations into mainstream programs and services may be the most effective strategy in many cases, many of the models profiled in the report directly or indirectly target nine overlapping categories of people who often need wraparound services and supports— some temporary and some ongoing—to succeed in the labor market. The nine groups are as follows:

- Disconnected youth;

- People with work-limiting disabilities;

- Single mothers and non-custodial parents;

- People with criminal records;

- Older workers who have been pushed out of the labor market due to economic dislocation;

- Disadvantaged immigrants, especially refugees and asylum seekers;

- Long-term unemployed workers;

- People in areas of particularly high unemployment; and

- People experiencing homelessness.

The notions of barriers to employment and hard-to-serve populations are not new. In fact, they have been a particular focus in the era following the 1996 welfare law. Researchers, with particular attention to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) population,10 have identified and defined these barriers in distinct but intersecting ways. One common approach is to categorize barriers into the following four overlapping, broad groups:11

- Personal and family challenges, including demographic characteristics, behavioral and physical health, trauma, physical and intellectual disabilities, family care responsibilities, and domestic violence;

- Human capital limitations, including limited education, training, work experience, and hard and soft skills;

- Logistical obstacles, including transportation, housing, and environmental factors such as neighborhood crime; and

- Legal limitations, including undocumented immigrant status and criminal records.

The lines between these overarching categories are not bright. These individual and structural barriers reflect a complex mix of socioeconomic dynamics, including actual and perceived work limitations. For example, a worker returning to his community after a lengthy period of incarceration may face more than one type of barrier. This framework attempts to build upon previous thinking about barriers, by expanding the list above to include additional crosscutting considerations relevant for subsidized employment program design. Figure 5 below shows an expanded list of barriers to employment. Program designers must think through what barriers potentially are appropriately and effectively addressable via subsidized employment programs, as well as the mechanisms through which such programs may lead to positive outcomes.

Figure 5. Employment Barriers

| Barrier | Description |

|---|---|

| Limited Skills and Education | Includes a lack of hard and/or soft skills, educational attainment that is less than a high school degree or equivalent, insuf cient formal work experience, etc. |

| Health and Disabilities | Includes behavioral health issues (such as mental illness, trauma, and substance use disorder), physical and intellectual disabilities, etc. |

| Family Responsibilities | Limited social resources and/or affordable care options or employer discrimination for workers who are pregnant or have care responsibilities for young children, family members with disabilities, elders, etc. |

| Criminal Justice System Involvement | Can result in limited access to employment, credit, public bene ts, and other crucial needs and services; ongoing legal issues; etc. |

| Limited Economic and Social Resources | Includes barriers related to unstable or unaffordable housing, transportation, limited social capital (e.g. professional networks and family and community resources/ capacity), etc. |

| Demographic and Other Personal Characteristics | Discrimination based on personal factors such as race and ethnicity, age, gender identity, sexual orientation, receipt of public bene ts, etc. |

| Immigration Status | Includes recent immigrants, especially refugees/asylum seekers; lack of lawful status; English language learners; etc. |

Some barriers stem primarily from identifiable deficits of hard and soft skills, resources, or experience on the part of an applicant. Someone lacking a high school diploma, for example, would fall into this category. Other barriers may result from prevailing prejudices, including those affecting assessments of risk on the part of employers. Someone with a disability or who is perceived as likely to have caregiving responsibilities may experience such barriers; this is also evidenced by the many communities of color that have faced well-documented labor market discrimination. Still other barriers, like unstable housing and limited access to transportation, may reflect structural challenges and represent serious logistical impediments to sufficient and stable employment.

Subsidized employment programs may help mitigate these barriers through varying mechanisms. For barriers stemming from identifiable deficits in potential job performance, they can offer work experience, training and support services, and hard and soft skills development. In some circumstances, subsidized employment programs may also increase the availability of jobs suited for people with particular barriers to employment. Subsidies may, for example, facilitate more opportunities for an employer to create or fill a position appropriate for applicants with intellectual disabilities or physical limitations. Although barriers related to systemic labor market discrimination may often not be addressable through subsidized employment, people with other employment barriers often face discrimination as an additional barrier—and subsidized employment initiatives may increase employment rates among populations facing systemic discrimination. That said, employers and other institutions relevant for the labor market should not receive incentives to simply obey legal protections and labor standards—such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s Title VII prohibitions against employer discrimination on the basis of sex, race, color, national origin, and religion and Title IX’s prohibition of sex-based discrimination by educational institutions.

Limited Skills and Education

Due to a number of factors, low-income and other disadvantaged populations may have had limited opportunities to obtain the skills, education, and experience desired by many employers in today’s labor market. These deficits may be in the area of hard skills (which includes technical, more easily-measurable skills such as educational credentials), or soft skills (which are less tangible—but equally as important— interpersonal and professional norm-oriented skills). Barriers pertaining to hard skills may be addressed by connecting individuals to services such as high school or General Education Development test (GED) completion support, vocational training, or skill certification. Soft skills can be taught informally as a complementary element of any hard skills-developing training, education, or on-the-job experience, or formally, through educational and other support services.

Educational attainment of less than a high school level may be among the most common barriers to employment among low-income workers.12 A lack of formal work experience, especially common among young adults, or a lack of recent work experience (e.g. those who are long-term unemployed) are related factors. A lack of relevant work experience may also be barrier, particularly for older workers, who may need additional training to adapt to new technological and other industry changes. Subsidized employment can help address employers’ reservations by lowering the financial risk of hiring, and potentially offsetting up-front hiring, orientation, and training costs, while providing steady work to participants that builds skills.

Health and Disabilities

Health problems, including those related to behavioral health, trauma, and physical, intellectual, and learning disabilities, can burden individuals and families in ways that negatively affect employment.13, 14 The social stigma attached to these conditions may inflect employer judgments about hiring risks associated with such individuals.15 In addition, physical, intellectual, and learning disabilities,16 whether stemming from tangible limitations on one’s capacity to work17 or a prospective employer’s assumptions about that capacity,18 may also pose barriers to employment. Employment programs that provide wraparound services such as transportation or occupational therapy could help expand the range of work options for individuals with physical limitations. They may also counterbalance the perceived risk or expense of hiring on the part of employers, and help overcome any stigma associated with disabilities.19 Finally, physical health limitations or disabilities may affect the availability of particular jobs themselves; employers may be more willing to tailor available positions to the requirements of applicants with physical disabilities if some of the initial cost is defrayed.

In the case of behavioral health issues (this includes mental illnesses and substance use disorders), subsidized employment programs that include mental health services, counseling for substance use disorders, and personalized case management may be particularly important here, as research suggests that such services, when well-provided, can help people with behavioral health issues achieve employment goals.20

Trauma can also pose a substantial barrier to employment. Trauma includes exposure to violence and abuse, such as sexual assault, domestic violence, and adverse childhood experiences. Research on the direct relationship between the experience of domestic violence and employment outcomes is inconclusive, but suggests that domestic violence can substantially magnify the negative effects of psychological distress on employment outcomes, and further suggests that these effects can be quite durable.21 Adverse childhood experiences have also been found to be associated with adverse employment outcomes.22 Fortunately, research suggests that adequate institutional and social support can help mitigate these outcomes and support people with traumatic experiences in their desire to acquire and keep high-quality employment.23

Family Responsibilities

Many workers who are pregnant or are caregivers for young children, family members with disabilities, or elders face unique challenges, including limited social resources and a lack of feasible care options. Sole caregivers—many of whom are disproportionately women—for young children in particular may find it especially difficult to afford reliable, high-quality care that allows them to fulfill the responsibilities of competitive employment.24 They may also face skepticism from prospective employers who either doubt their ability to commit sufficient time and energy to a job, or who make judgments about applicants’ responsibility and character based on their familial obligations. Some research suggests that employer discrimination based on pregnancy, a well-documented phenomenon in many areas of the labor market, may be even more acute for women who receive public assistance.25 Subsidized employment programs that can help arrange for quality child care can help address the first concern, while wage subsidies may lower perceived hiring risks.

Criminal Justice System Involvement

The collateral consequences of criminal justice system involvement are significant, limiting access to housing, education, public benefits, credit, and employment, among other crucial needs and services. Individuals with criminal records and incarceration experience have a particularly difficult time navigating the formal labor market.26 The criminal justice system, and prisons in particular, often make poor environments for gaining competitive work experience and professional socialization. People with criminal records may lack crucial skills, or not be properly socialized into formal work environments.27 They may also face ongoing legal issues and barriers that hamper their ability to participate fully in the labor market. Correctly or not, employers may also assign a greater risk premium to applicants with a criminal justice background, out of concern that applicants will either lack crucial skills or be prone to delinquency or criminality.28 Subsidized employment with appropriate wraparound services may help address these challenges by providing skills training, helping to navigate legal hurdles, and lowering perceived hiring risks on the part of employers.

Limited Economic and Social Resources

The populations of interest for this report will tend to have limited economic and social resources—a barrier to employment in and of itself. In particular, many individuals with serious or multiple barriers to employment are not part of families with the capacity to support them.29

Some of the other barriers to employment enumerated in this section may stem directly from this disadvantage of limited resources. Unstable housing is one such barrier to employment.30 People in deep poverty may be more likely to be homeless, which presents a host of practical and psychological barriers to preparing for competitive employment. Living far from employment opportunities or having limited access to transportation can also be a substantial barrier.31 Public transit options are limited in much of the country, and even where they are not, can impose a cost and time burden on low-income families. Work-appropriate clothing may be beyond the financial reach of some jobseekers. Other barriers may have little inherent relationship to socioeconomic status (e.g. child rearing) but nevertheless are magnified by a lack of resources.

People who are in poverty, and especially deep poverty, may face a host of challenges to labor market success that are more easily overcome by those with access to greater resources. Wraparound services that address these resource deficiencies may be especially crucial for these individuals.

Demographic and Other Personal Characteristics

Some barriers to securing employment arise almost entirely from prevailing prejudice based on personal characteristics. Race and ethnicity, for example, have been consistently shown to affect an individual’s chances of being hired, even when controlling for other potentially relevant factors.32 One prominent study that analyzed barriers for mothers who are recipients of TANF cited this issue of employer discrimination based on race, gender, and receipt of public assistance as a major obstacle to securing and maintaining employment.33 Gender is also a relevant barrier, particularly in professions where an applicant’s gender is viewed as atypical.34 LGBT identity is also associated with greater risks of low pay and poverty.35 Age, whether for older or younger workers, has also been shown to influence employer hiring decisions.36 One study, for example, found “robust evidence of age discrimination in hiring against older women.”37 Beyond hiring, workplace discrimination poses a barrier to maintaining employment.38 The first step to reducing barriers related to discrimination in particular is to enact and enforce adequate legal protections. Nevertheless, subsidized employment, combined with appropriate supports, may be a promising strategy for helping to increase employment among groups most likely to experience discrimination in the labor market.

Immigration Status

Having arrived to the United States recently or without lawful status often poses substantial barriers to securing competitive employment. Lack of lawful status poses obvious challenges in securing stable formal employment (employers are often reluctant to hire workers lacking lawful status due to legal risks) and being paid fairly. Some recent immigrants may not have skills that are easily transferable to the U.S. labor market. English-language learners will face especially limited prospects.39 Through paid work experience, on-the-job training, and wraparound services, subsidized employment may help address these barriers.

Figure 6. Employment Barriers and Primary Subsidized Employment Strategies

| Barrier Typer | Population With Barrier | Primary Subsidized Employment Strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limitations in Workers’ Overall Productivity | Human Capital |

Limited Skills and Education | OJT; Work Experience |

| Immigration Status: Recent Immigrant, especially Refugee/Asylum Seeker | OJT; Work Experience | ||

| Personal and Logistical | Behavioral Health | Wraparound Services; Work Experience | |

| Limited Economic and Social Resources: Transportation, Housing Stability, etc. | Wraparound Services | ||

| Family Responsibilities | Wraparound Services | ||

| Health and Disabilities: Work-Limiting Physical Health Challenge or Disability | Alternative to Competitive Employment | ||

| Systemic Discrimination by Employers* | Legal | Immigration Status: Undocumented Status | General Employment Subsidy |

| Criminal Justice System Involvement | General Employment Subsidy | ||

| Demographic | Healtha nd Disabilities: Apparent Disability | General Employment Subsidy | |

| Age | General Employment Subsidy | ||

| Race and Ethnicity | General Employment Subsidy | ||

| General Employment Subsidy |

|

Figure 6 organizes specific barriers discussed above into two broad categories: limitations in workers’ overall productivity due to human capital or personal and logistical barriers, and systemic discrimination by employers based on legal or demographic factors. It then matches these barriers with the primary subsidized employment strategies (discussed in more detail later in this framework) especially well-suited to address them. To be sure, many disadvantaged workers will have multiple barriers best addressed through multiple strategies. In addition, individual subsidized employment strategies (general employment subsidy, OJT, work experience, wraparound services, and providing an alternative to competitive employment) may be more effective in combination with each other. At their core, all subsidized employment programs offer a general employment subsidy, which may be especially helpful for increasing the hiring of workers facing systemic discrimination in the labor market. To be clear, though subsidized employment programs are not intended to and are not necessarily likely to be especially effective in addressing discrimination, they nevertheless can help people facing those barriers and increase employment among groups experiencing labor market discrimination. However, subsidized employment programs may be best suited to address barriers that in some form or another limit a worker’s overall employment productivity.

Competitive Employment vs. Income Support

Some programs have the specific goal of connecting participants with competitive (unsubsidized) employment. Others may not intend this to be the end goal for all participants, but rather seek to provide income support through employment to those for whom personal and socioeconomic barriers—or macroeconomic circumstances, during recessionary periods—make competitive employment difficult. Programs can of course attempt to serve both purposes and populations.

Scale

The ideal design of a subsidized employment initiative may depend on a program’s scale. Large-scale programs may require particular attention to concerns about worker displacement.40 Scale may also affect the feasibility of intensive wraparound services, and depends heavily on the ability to partner with employers to offer a sufficient number of positions.

Program Characteristics

Once a program’s purpose, including its target population, is established, a range of program characteristics need to be determined to achieve the program’s goals. Below, options for subsidies, work placements and expectations, training, and the provision of additional services are discussed briefly.

Subsidy Configuration

Subsidies can be configured in a variety of manners, with differential consequences likely for different arrangements, with regard to what exactly is being subsidized, to what extent, and for how long.

Subsidy Type

Subsidies ordinarily offset wage costs directly, but OJT (or other training closely intertwined with a specific job), benefits, and even human resources and overhead expenses may also be offset.

Subsidy Depth

Subsidies can fully offset or only partially offset an employer cost—typically wages, but sometimes on-the-job training or overhead. In addition, subsidies can be disbursed at a steady rate over the course of the subsidy period or taper off, reducing the percentage of the wage subsidized over time potentially affecting the likelihood of an employer keeping participants on the job once program supports end.

Subsidy Length

Subsidies in programs examined in this report vary considerably in the length of time they last, with some ending after only a few months and others continuing for more than a year. While systematic evidence on the impact of subsidy duration is lacking, it is notable that the rigorously evaluated programs in this scan that have longer subsidies have the most consistent record of improving employment and earnings.41 This potential benefit may need to be balanced against additional costs incurred for longer-lasting subsidies. The timing of pay (e.g. whether daily, bi-weekly, etc.) may also be an element for consideration.

Work Placements

Program designers face key choices about which employers to engage and what employers’ legal role should be. Considerations include the long-term placement strategy, the sector of employment, employer size, who the employer of record (sometimes a third party aside from the employer) should be, and the availability of opportunities to advance within an organization or industry.

Possibility of Rollover

Some programs aim to find jobs that are explicitly transitional. The purpose of the job (from the participant’s point of view) is to build work experience, skills, and financial stability, with the expectation that they will find competitive employment elsewhere once the subsidy ends, perhaps with additional assistance (see “Employment Search and Retention Services” below). With this design it may be possible for administering organizations to develop stable relationships with employers who can cycle many participants through the same or similar subsidized positions over time.

Other programs combine subsidized employment and permanent job placement into a single step, seeking to place participants in jobs with the potential to continue (or “roll over”) after the subsidy ends. Wage subsidies in this model are meant to provide participants with a “trial run” with an employer that might not otherwise have been open to hiring them. This model may raise particular concerns about displacement, as it may be difficult to induce employers to create jobs that would not exist but for the subsidy if such jobs are expected to continue unsubsidized. There is also a question of scale, and whether administering organizations will have the capacity to regularly find new permanent openings in the labor market.

These two strategies are not mutually exclusive—it may be possible for programs to apply the two models in parallel, taking into account labor market conditions and the specific needs and skills of target populations and individual participants.

Employment Sector

Some programs limit-subsidized jobs to public or non-profit employers. Others focus on connecting participants with for-profit, private sector jobs. Others provide subsidized employment in two or all three sectors. Non-profit or public employers may be more willing than for-profit employers to work with individuals that have multiple or serious barriers to employment. However, in some cases, they may have less flexibility in permanently expanding their payroll, may face weaker incentives for improving worker productivity, and may be less likely to help workers develop transferable skills, thus potentially reducing the chances that participants transition to unsubsidized jobs. These distinctions are likely overstated here, but they nevertheless may affect the extent to which subsidized employment mirrors competitive employment and offers workers experiences that can be lead to future labor market success.

Employer Size

Targeting or limiting programs to smaller employers may also allow closer monitoring and deeper understanding of the employers, in turn reducing the risks that employers hire subsidized workers in place of unsubsidized workers they otherwise would have hired. Some practitioners have found that small businesses are more likely to have flexible hiring policies and are more interested in subsidized employment programs, especially when an intermediary—not the business—is the employer of record, thus reducing administrative and fringe expenses for businesses.42 However, limiting employer size may limit the scale of the program and participants’ advancement opportunities.

Employer of Record/Payroll

Some programs require employers to place participants on their payroll, while others allow for intermediary service delivery organizations to serve as “employer of record” for the length of the subsidized job. They may also vary in the status given to participants at work, often as regular employees, but sometimes as interns or volunteers. These choices have implications for Unemployment Insurance (UI), workers compensation, health insurance, and other benefits and protections. These decisions affect the administrative and financial burden on participating employers, in turn affecting their willingness to participate.

Advancement Opportunities

When subsidized jobs are intended to be transitional, advancement opportunities and connections with career pathways are important. Some programs may seek to target specific employers or industries with established career ladders along which entry-level employees can advance. As with other factors that can limit subsidized job placements, emphasizing advancement opportunities may be in tension with scale.

Work Structure

The particular work experience of any subsidized jobs program will depend on a number of structural features, including the nature of worker responsibilities, supervision, and team environment.

Worker Responsibilities

Programs vary significantly by the expectations placed on workers, often reflecting fundamental decisions about the extent to which the work experience should mimic competitive employment. One choice is whether a program will stipulate part-time or full-time work. Some programs may require only a few hours of a work each day for four days a week, with training or other services on the fifth day, while others may require a standard 40-hour work week. Such expectations can change over the course of a placement, as exemplified by some of the models reviewed in this report. Over time, participants might be expected to match the responsibilities of unsubsidized employment. The appropriateness of this approach may depend on target populations, as well as the requirements of participating employers.

Supervision

For some participants with barriers to employment, the intensity of supervision (over and above the standard in competitive jobs) may matter for successful integration and socialization into norms of work. More intensive supervision will tend to raise program costs and limit scale, however.

Team Environment

Some programs place workers into individual assignments, while others use a team or “work crew” approach to place workers as a group. Group accountability and camaraderie may help some participants integrate more easily into professional settings, but may not allow for more intensive supervision. However, the potential benefits of these approaches have not been systematically tested.

Training

Many subsidized employment programs offer opportunities for formal training, which can vary by type and structure by which it is delivered.

Training Type

The nature of training provision varies among programs. Some offer subsidized employment with no additional (hard and soft) skills development beyond what participants glean from their experience on the job. For some populations with multiple barriers to employment, formal training in soft skills and professional norms, potentially before job placement, may matter for long-term success. Other programs might offer training in more advanced or industry-specific skill-sets.

Training Structure

Among programs that do provide training, there are differences in how that training is integrated into the subsidized employment opportunity. Some educational institutions and programs explicitly subsidize work opportunities that provide OJT. Others provide formal training outside the work environment, either before job placement as part of the orientation period, or in conjunction with the subsidized job itself.

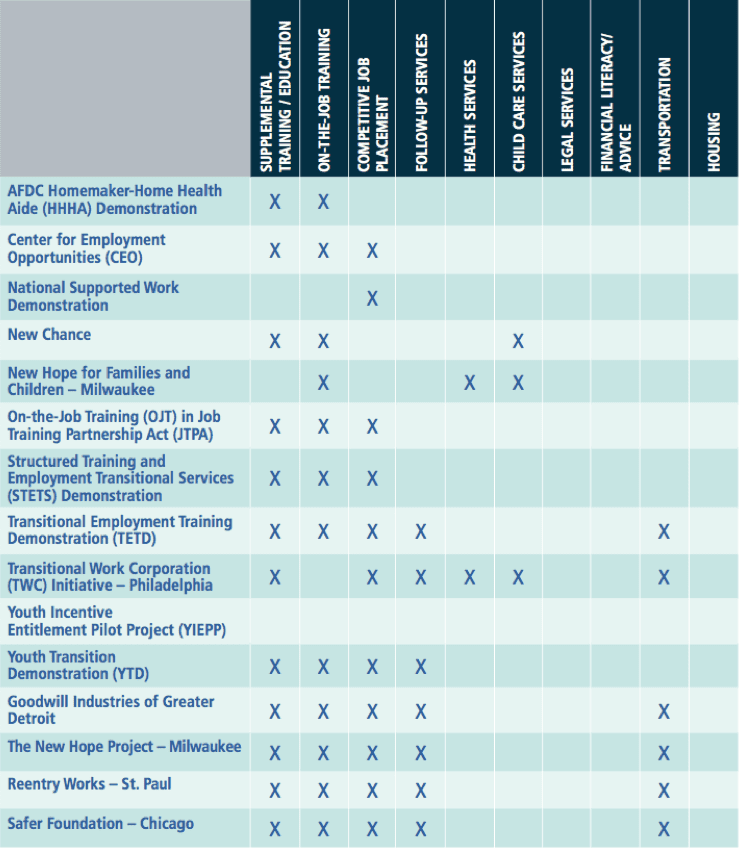

Additional Services

To address additional challenges, subsidized employment programs may offer complementary wraparound services and follow-up job search and retention services.

Wraparound Services

The specific package of wraparound services provided to participants may be important to program success or failure. Services may be tailored to individuals, or to target populations as a whole. For example, subsidized jobs and paid work experience programs may provide legal services to recently-released prisoners, treatment and counseling for people with substance use disorders, or child care to working parents. Other wraparound services may include life skills education, cognitive behavioral therapy, financial counseling, transportation assistance, housing referrals, or other supports that help stabilize disadvantaged workers and their families.

Employment Search and Retention Services

Once participants exhaust their job subsidies, many programs continue to provide follow-up services, either to assist with a job search (for transitional jobs programs) or to help with job retention (for subsidized employment programs) or both.

Review of Models

Review of Models: 40 Years of Evidence and Promise

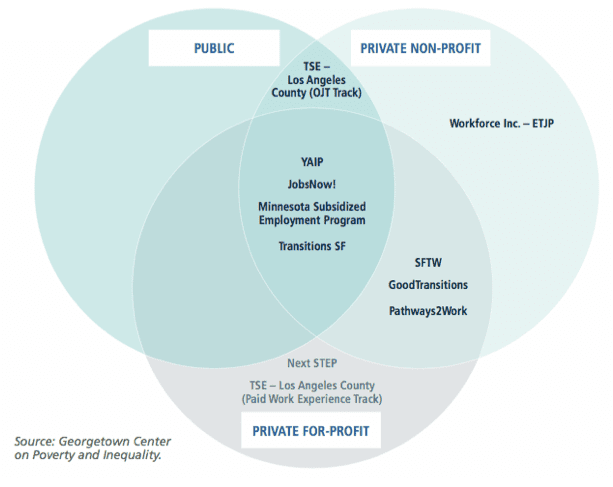

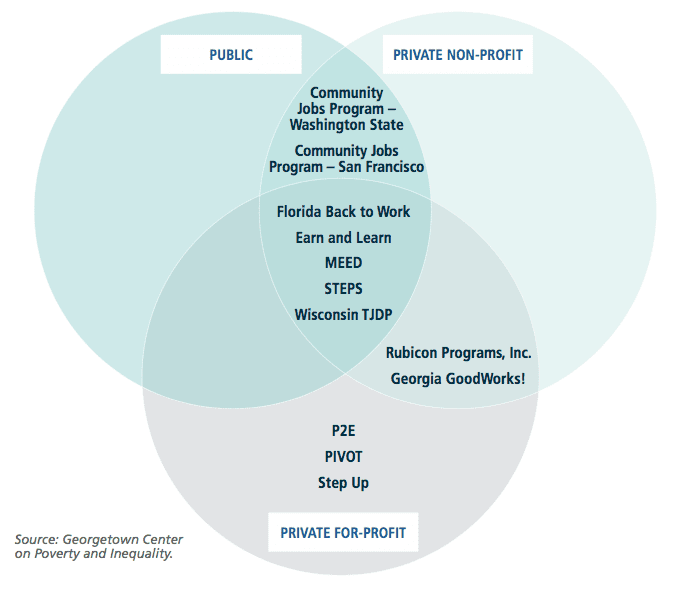

This section highlights key findings from an extensive scan of subsidized jobs programs, and then describes a number of specific models in place currently or in recent decades (since 1975) with a focus on disadvantaged populations. In some cases, subsidized employment is at the very core of the model, while in other cases, it is merely an option in a broader employment and training program and is taken up by few participants. This review is followed by the report’s final section, which offers recommendations for policymakers and practitioners.

Subsidized employment models are grouped into the following subsections below (within each subsection, programs are ordered alphabetically):

- Rigorously Evaluated Models;43

- Models with Rigorous Evaluations Underway;

- Notable Models without Rigorous Evaluations Completed or Underway; and

- Rigorously Evaluated Unsubsidized Employment and Work Experience Models.

The review then describes several notable unsubsidized employment and work experience (paid and unpaid) programs that may offer constructive lessons on program and policy design and implementation. Finally, the report briefly reviews a few promising youth-focused subsidized employment models.

Promising models should show improved outcomes for participants under normal economic circumstances.44 During recessions, supportive paid work opportunities can help stabilize the economy, tighten the labor market, and maintain labor force attachment. In times of general economic prosperity, subsidized employment and paid work experiences are nonetheless helpful for people needing extra help to get into the labor market and for people getting paid work experience as a key part of an educational program. Ideally, promising models would be rigorously evaluated to show impacts, i.e. participant improvements that are attributable to the program. Even effective models are not necessarily socially cost-effective, which requires that the model has both positive impact and results in net savings to society.

Box 1. Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA, 1973-1982)

One of the largest—if not the largest—subsidized employment programs in recent history, Public Service Employment (PSE) under the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA, 1973-1982), was not rigorously evaluated before its expiration.45 PSE offered not only public service employment, but also classroom training, subsidized OJT, and work experience, reaching approximately 360,000, 100,000, and 300,000 people respectively in Fiscal Year 1980 for an average of about 20 weeks per participant.46 As a result of the 1974-1975 recession, PSE developed a significant countercyclical emphasis.47 CETA was intended to target disadvantaged individuals, though there was criticism— especially in CETA’s early years—that the program assisted the relatively advantaged among disadvantaged target groups.48 Little can be said with certainty about CETA and PSE, but non-experimental studies suggest sometimes contradictory findings, with one analysis suggesting positive effects only for women in classroom training, OJT, and public service employment (not work experience),49 and another analysis of the impacts of training on men found large positive effects from classroom training and smaller, positive effects from OJT.50

Findings and Observations

Broad generalizations about the effectiveness of subsidized employment and paid work experience programs must be made with care, as the range of programs that have existed have distinct purposes and goals, target different populations, and represent different commitments of time and resources. Some interventions show little impact on post-program employment, but nevertheless achieve other worthy goals, such as increased earnings, reduced dependence on public assistance, improved skills, or reduced criminal recidivism. Further, a number of subsidized employment demonstrations launched in 2010 by DOL and HHS are still being analyzed (initial impact evaluations will not be published until 2016). It is especially important to keep in mind that even the best evaluations rarely isolate causal impacts with absolute certainty. Those caveats aside, however, some overarching findings and observations can be made:

- The number of disadvantaged people willing to work consistently exceeds the number in competitive employment. The history of subsidized jobs programs underscores this reality, regardless of macroeconomic circumstances. YIEPP (Youth Incentive Employment Pilot Projects), which began during an economic expansion, and the TANF Emergency Fund (TANF EF), which existed entirely during the deepest recession since the Great Depression, together demonstrate the substantial demand among workers for employment opportunities beyond what is otherwise available. This response by potential workers also reflects the need for greater income among those left out of the competitive (unsubsidized) labor market.

- Subsidized employment programs have successfully raised earnings and employment. This effect is not universal across programs or target populations, but numerous rigorously evaluated interventions offer clear evidence that subsidized employment programs can achieve positive labor market outcomes. Some of these effects derive from the compensation and employment provided by the subsidized job itself, but there also is evidence that well-designed programs can improve outcomes in the competitive labor market after a subsidized job has ended.

- Subsidized employment programs have benefits beyond the labor market. Fundamentally, subsidized jobs and paid work experience programs provide a source of both income and work experience. A number of experimentally-evaluated subsidized employment programs have in turn reduced family public benefit receipt, raised school outcomes among the children of workers, boosted workers’ school completion, lowered criminal justice system involvement among both workers and their children, improved psychological well-being, and reduced longer-term poverty; there may be additional effects for some populations, such as increases in child support payments and improved health, which are being explored through ongoing experiments.

- Subsidized employment programs can be socially cost-effective. Of the 15 rigorously evaluated (through experimental or quasi-experimental methods) models described in this report, seven have been subject to published cost-benefit analyses. Keeping in mind that more promising and effective models are more likely to lead to such analyses, all seven showed net benefits to society for some intervention sites (for models implemented at multiple sites) and some target populations. Four of these seven models were definitively or likely socially cost-effective overall.

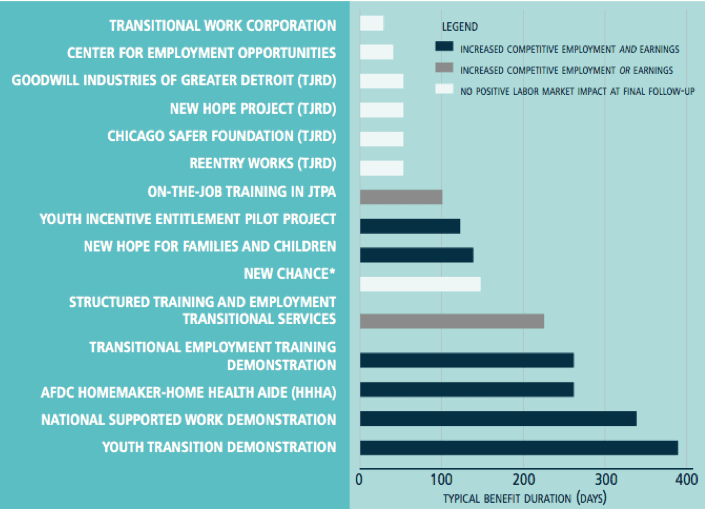

- Subsidized employment programs with longer-lasting subsidies and services appear to be more likely to raise employment and earnings. No research to date has isolated the impact of benefit duration within a subsidized jobs program. However, this pattern among rigorously evaluated programs—with interventions that typically lasted more than 14 weeks having a high likelihood of effectiveness—suggests that the role of benefit duration merits further investigation (see Figure 7). Program evidence from the Youth Transition Demonstration (YTD) found that projects that provided “more hours of employment-focused services” generated the most positive impacts on employment.

- More innovation is needed to assist young people disconnected from the labor market through subsidized employment. Results from the National Supported Work Demonstration and the On-the-Job Training (OJT) initiative under the Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA), for example, show no impact on employment, drug use, or criminal activity among younger participants. This finding dovetails with the results of a recent cross-national meta-analysis that finds young people to be the least amenable to active labor market policy interventions.51 Further, there is evidence from other programs that positive earnings and employment effects of subsidized employment can attenuate with time.52 That said, results from YIEPP suggest that subsidized employment can make a difference in both earnings and employment for some youth, at least over a period of 3-15 months post-intervention.53 Analysis of the Youth Transition Demonstration (YTD) suggests that interventions that provide a range of services beyond transitional employment may be especially important for younger populations. Upcoming impact evaluations from some projects under HHS’s ongoing Subsidized and Transitional Employment Demonstration (STED) may provide further evidence as to which interventions are most effective with this age group.

- Older adults remain understudied and underserved. None of the programs examined here specifically target older adults who are disconnected from the labor market. Further, relatively few older adults participated in programs for which they were technically eligible. There is thus a paucity of both information about and support for successful interventions for this population. This reality is of particular salience, as policymakers grow concerned with shrinking labor force participation among older workers. Subsidized employment may represent a desirable way to provide income support to older and disabled workers not receiving disability or retirement benefits.

- Subsidized employment can help people with intellectual disabilities gain independence and earning power; the broader spectrum of disabilities remains understudied. The Transitional Employment Training Demonstration (TETD) (1985-1987) and the Structured Training and Employment Transitional Services (STETS) (1981-1983) both demonstrated positive effects on labor market participation and/or earnings among participants with intellectual disabilities. The role of subsidized employment and paid work experience in assisting those with other kinds of disabilities is not addressed by any known research.

Figure 7. Benefit Duration and Labor Market Impact of Rigorously Evaluated Subsidized Employment Programs

Note: These data are derived from the typical duration of subsidized employment plus training services as reported in program evaluations or other program materials. Effectiveness is based on the final follow-up. Transitional Work Corporation had significant effects during the first year following program entry, but those effects faded by the four-year follow-up. TJRD refers to the Transitional Jobs Reentry Demonstration.

*New Chance’s impacts were evaluated in comparison to a control group, which did not participate in subsidized employment but did receive an array of other support services. In addition, the paid internship was arguably not a significant component of the program.

Source: Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality.

More work is clearly needed to isolate the impacts of various facets of subsidized employment. Strong employer engagement, the provision of wraparound services, longer-term post-placement retention services, and other features of effective programs also appear promising as key ingredients and merit further (experimental) examination, as research thus far has shed little light on specific factors and their impacts to date. Other program design elements that may warrant additional testing include pre-training, program entry screening processes, matching processes, and peer support mechanisms. However, the record as it stands indicates that such programs, by increasing employment opportunities, can be effective tools to combat poverty, persistent unemployment, and other harmful social outcomes.

Rigorously Evaluated Models

The following models have been evaluated through an experimental or quasi-experimental study, and final results are available. Figure 8 presents a summary view of the rigorously evaluated models (listed in alphabetical order).

Figure 8. Summary Table: Rigorously Evaluated Models

| Program | Years | Population(s) Targeted | Paid Work Experience & Supports | Outcomes (positive effects bolded) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFDC Homemaker- Home Health Aide (HHHA) | 1983 – 1986 | AFDC recipients, primarily single mothers | Occupational training as a home health aide; supervised OJT; 12 months’ subsidized employment | (An average of) 22 months after program entry,* earnings and nonsubsidized employment increased |

| Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) – New York City | 1970s – present; evaluated 2004 – 2005 | Formerly incarcerated | 5-day pre-employment class; subsidized positions in work crews; professional development; job placement assistance | 36 months after program entry, did not increase earnings, but did signi cantly reduce recidivism, especially among high-risk individuals |

| National Supported Work Demonstration | 1975 – 1979 | Multi-year AFDC mothers; recovering addicts; formerly incarcerated; young high school dropouts | Subsidized supervised transitional jobs for 12-18 months; job placement assistance | 19-36 months after program entry, improved labor market outcomes (earnings and employment) for most participants; reduced recidivism; no lasting effect for high school dropouts |

| New Chance | 1989 – 1992 | Young single mothers who dropped out of high school | Pre-employment training; life skills training; part-time internships (limited participation); ABE; GED preparation; child care; counseling and other community- based services | 42 months after program entry, no positive labor market effects, but some positive effects on GED receipt, college education; impact dif cult to isolate because control group also received some services |

| New Hope for Families and Children – Milwaukee | 1994 – 1998 | Low-income people seeking full-time work | Earnings supplement; subsidized health insurance; subsidized child care; community service jobs for persistently unemployed recipients |

8 years following program entry, positive effects on earnings, employment, poverty, marriage rates, mental health, child achievement and behavior; effect faded for some by year 3; low bene t uptake rate |

| On-the-Job Training (OJT) in Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA) | 1983 – 2000 | Welfare participants; young people not in school; young males arrested since age 16 | Service tracks included: classroom training; subsidized OJT and JSA | 30 months following program entry, small positive effects on earnings for adults; positive effects on GED receipt for young women; no positive earnings effect for youth/young men |

| Structured Training and Employment Transitional Services (STETS) Demonstration | 1981 – 1983 | Youth with intellectual disabilities ages 18-24 | Training; supervised work and OJT; job placement assistance | 22 months after program entry, increased earnings, but did not increase in employment |

| Transitional Employment Training Demonstration (TETD) | 1985 – 1987 | SSI recipients with intellectual disabilities, ages 18-40 | Subsidized employment; externally-administered OJT; post-placement retention services | 36 months after program entry, increased earnings and employment |

| Transitional Work Corporation (TWC) Initiative – Philadelphia | 1998 – early 2010s | Long-term and potential long- term TANF recipients, especially single mothers | Subsidized employment; training; behavioral health services | 48 months after program entry, earlier 12-month positive effects from on employment, earnings, and TANF receipt had faded faded with time; high attrition rate after program entry |

| Youth Incentive Entitlement Pilot Project (YIEPP) | 1978 – 1980 | Low-income or welfare- household youth, especially African American and Hispanic |

Subsidized employment | Approximately 36 months after program entry, increased employment, especially for African American males; smaller effects for Hispanic females; no effects for Hispanic males; no effect on school graduation rates |

| Youth Transition Demonstration (YTD) | 2006 – 2012 | Individuals ages 14-25 receiving or at risk of receiving SSI or SSDI | Subsidized employment; on-the-job-training; volunteer work; job shadowing; job placement assistance | 36 months after program intervention, intense interventions had positive impacts on employment and earnings; more ambiguous but still positive ndings on criminal justice system interaction |

| Transitional Jobs Reentry Demonstration (TJRD) | ||||

| Goodwill Industries of Greater Detroit | 2007 – 2008 | Recently incarcerated men | Transitional subsidized employment at Goodwill light manufacturing plant; job placement assistance; follow-up services | 24 months after program entry, no signi cant effect on labor market or recidivism |